On Building - our essay from the NFT Taschen Book

TLDR: a good summary of infrastructure and the history of NFTs towards ERC-721 as told by its protagonists

This past week, Taschen unveiled the On NFTs book, which us, among many other infinitely talented people contributed too. Much has been said about the book already.

Our essay was written in early 2022, and it is a snapshot of 5 years of building NFT infrastructure (before getting steamrolled by the many disasters of that year). While I am happy the book has finally come out, I am concerned that our essay will not reach many due to the high cost of the book. So, in the spirit of open-source, collaboration and decentralisation (that Taschen and the book’s editor, Robert Alice, have mentioned many many times), I’m making our essay available through this humble newsletter.

Ps. the footnotes have actually a lot of excellent info, and the images we used to illustrate are from private e-mails (consensually shared), message boards, and more historically important tidbits.

On Building

By Maria Paula Fernandez, Simon Denny, and Adina Glickstein

“Currency is the least interesting thing you could build with this technology.”

– Anil Dash and Kevin McCoy’s Monegraph presentation for Rhizome 7x7, 2014

INTRODUCTION: CRITICS AND HACKERS

At the beginning of the pandemic, Marc Andreessen penned a blog post decreeing that, in the wake of this black swan disaster, the “Time to Build” was upon us. His injunction – take the initiative to create new structures that actively address the lack of ingenuity and pragmatism in private and public sectors alike – came from a firsthand conviction that critique is best served by actively making anew. In 1992, Andreessen, then an undergrad on the brink of his B.S. in Computer Science, co-developed Mosaic, one of the first user-friendly web browsers. Mosaic evolved into Netscape, marking the start of the commercial internet and ushering in Web 1.0 as we know it. Fast-forward to 2022 and Andreessen’s firm, a16z, is one of the most notorious (and foresighted) VCs on Sand Hill Road, boasting a portfolio stacked with many of the web 2.0 platform giants that organize most of our browsing hours today, alongside numerous major players in the emerging world of Web3. Fear him, revile him, or respect him, Andreesen’s philosophy has long been coupled with action; as a hacker, an instigator and a builder, he embodies the ethos he promotes.

This emphasis on building, which lends its title to this essay, harmonizes with the history of Web3, where critique often takes the shape of creation. The artist-researcher-theorist Jaya Klara Brekke has outlined the figure of the “hacker-engineer”as a central protagonist in the infrastructural development of Web3 technologies, grounding the making of contemporary digital network economies in cypherpunk and hacker lineages(1). This holds true in the NFT space, where new possibilities for making and distributing digital art have come to light through an iterative, decentralized process, as much as anywhere else in Web3. At the most basic, blockchains of all kinds offer the potential to serve as public, immutable ledgers maintained by the people using them rather than being overseen by a top-down authority – whether that be a state, a bank, an auction house, or a gallery. And as Brekke’s observation stresses, hacking and building are deeply intertwined; not so much opposed categories as pieces of the same process.

Building, conceived of in this way, takes the form of a critical gesture. It heeds Andreessen’s call to bring the worlds we want to see into existence, no matter our technical background; to make new things instead of just commenting on the extant system from some imagined position of intellectual remove. The role of critique underwent a similar shift at a critical point of art-historical inflection long before Web 3: in 1968, Lucy Lippard and John Chandler wrote that, following the conceptual turn, the role of criticism must be recast: “Judgment of ideas is less interesting than following ideas through... If the object becomes obsolete(2), objective distance becomes obsolete.” As the “art object” grows increasingly immaterial, they argue, critique ought to become more tangible, more focused on advancing new ideas in practice.

NFTs, of course, are not “immaterial” – they are made of software, files, and networks, all of which take physical forms; they have a spatial, material and carbon footprint. But they may well be situated in the history of conceptual art that Lippard and Chandler outlined (as indeed they are elsewhere in this book), and the unexpected resonance between these art historians’ observations and Andreessen’s call to build is revealing. The infrastructural history of NFTs has been shaped by the active efforts of interested parties, from artists to technologists and many figures overlapping or somewhere in between, collectively and dynamically nudging existing technology towards new ends and broadening the field of future possibility in the process.

A note on methodology: to reflect on the emergence of NFT infrastructure – and to show how it came to exist through the labor of communities and networks – is necessarily to set forth some kind of timeline. This is a pragmatic choice, enabling us to suggest that these developments often happened in conversation with each other, building on – knowingly or not; critically or in homage to – the projects that came before(3). It’s not our goal to identify what constituted the first “true” NFT project. That question is hotly contested, and is also somewhat beside the point. Likewise, the precise dates of new infrastructural developments – especially in the Ethereum ecosystem, and wherever else community proposals and review processes are concerned – can be amorphous(4). Rather than staking a claim about which of the numerous inventive and prescient early tokenized artworks was the earliest, the most significant, or the truest to NFTs’ present form, we offer a (necessarily selective) historical sketch of the infrastructural developments, carried out by artists and technologists cross-pollinating through entangled, cybernetic loops, that expanded the space of possibility for NFTs as we know them today to come into being – and the new directions they have opened up towards a future still under construction.

BITCOIN (IM)PURISM

The history of hacker-engineers and artistic innovators paving the way towards NFTs traces back to the web’s earlier history in varied and often oblique ways through more than just Mosaic and a16z. In January 1993, Hal Finney – who would later contribute to Bitcoin’s development – sent a CompuServe email blast imagining a market for “cryptographic trading cards”, sketching out one use-case for “digital cash”. By 2012, four years after the Bitcoin network’s launch, Finney’s speculative sketch was already something of a reality. Yoni Assia, Lior Hakim, Meni Rosenfeld, Rotem Lev, and Vitalik Buterin (who was, at the time, a secondary school student writing for Bitcoin Magazine) authored a whitepaper that outlined a protocol for experimenting with colored coins, or ways of adding information to Bitcoin transactions, “coloring” tokens to represent their connection to other assets(5).

In a similar vein, but with more elaborate functionality, Counterparty, an open-source project initially designed as a peer-to-peer financial platform on top of the Bitcoin blockchain, made it possible for users to create, name, and issue their own tokens. Launched in 2014, it created the possibility of “broadcasting”, or publishing text and data through Bitcoin transactions. Like any Bitcoin block, each Counterparty broadcast is timestamped, browsable, and permanently stored on the ledger(6). Adam Krellenstein, one of its co-founders, explained in an email to the authors of this essay that the idea for Counterparty came from initiatives around the same time like Mastercoin, which sought to build a distributed financial system using Bitcoin with additional affordances for different kinds of assets (7). Art and digital collectibles quickly became one such asset class, and are still traded on Counterparty’s decentralized exchange (DEX) today, though in relatively smaller volume than on Ethereum.

Counterparty broadcast tokens formed the basis for early tokenized art projects like NILICoins, where Israeli artist Nili Lerner issued 1000,000 “Art-Coins”, appropriating brand names like Coca Cola and eBay, all backed by the value of her existing physical artwork. Lerner announced the project on a BitcoinTalk forum in September of 2014, where it was met with modest excitement. The prevailing response amongst BitcoinTalk commenters, though, was chagrin – “So the fact is that you, as an artist, are short of money. You wanna find some in the crypto world?” – illustrating the Bitcoin community’s hesitancy towards projects that used the blockchain for anything other than cryptocurrency trading (and perhaps equally, the perils of being too prescient – e.g., early to market(8)).

With Counterparty, it was also possible to issue unique 1/1 tokens, as JP Jannsen did in a broadcast on 12th June 2014 dedicated to his girlfriend (and now wife, testifying to the immutability of the world’s oldest non-fungible asset, true love), Olga. Setting and locking the supply to one indivisible token, Jannsen minted a declaration to Olga in a transaction bearing the description, “My Eternal One & Only”. Later, in 2015, he added a pencil sketch, depicting him and Olga locked in an amorous embrace, onto the token – cleverly deploying an early attempt at making unique and ownable artworks on the blockchain.

Roughly contemporaneous with these Counterparty experiments, in May of 2014, Anil Dash and Kevin McCoy made history from the auditorium of New York’s New Museum, at Rhizome’s Seven on Seven conference. The pair, linked for the annual flagship event that puts artists and technologists together for a ten-hour hackathon, took to the stage to debut Monegraph – a prototype for registering ownership of digital artworks using Namecoin, an early Bitcoin fork. Digital artists, they observed, were limited by the contradiction that building visibility, and thus financial viability for their work, requires letting it circulate openly online; in essence, giving it away for free. Meanwhile, Bitcoin, per their assessment, was plagued by a lack of imagination: “Currency is the least interesting thing you could build with this technology” read one slide of their presentation in a sideswipe at the purists who saw it strictly as a financial medium.

Monegraph – a portmanteau of “monetized graphics” – offered a solution for verifying the uniqueness and provenance of digital work, making art saleable without constraining its circulation. Each Monegraph claim consisted of a hash, a URL representing the actual artwork, and an assertion of the title to the work in plain, readable language; it harnessed Twitter tie-ins for its identity-verification layer. Demoing the protocol onstage, McCoy sold Dash a GIF, “cars.gif” (co-created with his wife, artist Jennifer McCoy), together with its corresponding Monegraph title, in exchange for the four bucks in cash that he had on him. Foresighted as it may have been, Monegraph’s creators insist that they did not invent NFTs as we presently understand them. “By doing a public, visible demonstration, we took the most likely path of preventing the technology from harming artists by removing the ability for others to patent it later in an exploitative way”, Dash reflected in 2021, emphasizing Monegraph’s origins “in a context of a non-profit, artist-centered demonstration held at a museum.(9)” Again, the question of who – or what – “invented” NFTs is less important than the ecosystem that facilitated their development, and the recognition that their underlying infrastructure was produced through a process of hacking and ad-hoc iteration: communities, networks, and artists taking the responsibility to create new tools into their own hands.

SELLING BITS OF CULTURAL IP

The idea of buying and selling bits of cultural IP, often hinging on in-group knowledge, of course predated the blockchain through media like trading card games – and the advent of Bitcoin, conferring demonstrable digital scarcity to secure these exchangeable assets’ status as “rare”, fueled their development even further. An exemplary case of the union between niche memes and digital scarcity came in September of 2016 with the advent of Rare Pepes, Bitcoin-secured cards bearing the figure of the infamous cartoon frog, capitalizing on the speculative trade of dank memes in imaginary Reddit markets (such as /r/MemeEconomy). Unlike the Spells of Genesis trading cards before them, which were situated within a larger game world, Rare Pepes did not exist inside a game – the market itself was the game. Users could submit their own cards, complete with original artwork; the forum for frog-exchange thus became a community, centered not just on cards’ exchange, but on their creation. Rare Pepe Wallet, which hit the scene on 15 September 2016, offered an accessible user interface for the purchase and sale of these cards, and could be seen as a progenitor to the NFT marketplaces of today. It also pioneered the idea of access tokens, enabling the holders of certain Pepe cards to unlock gated bonus content. Rare Pepe Wallet is still in operation half a decade later, and Rare Pepes are traded on Counterparty to this day (10).

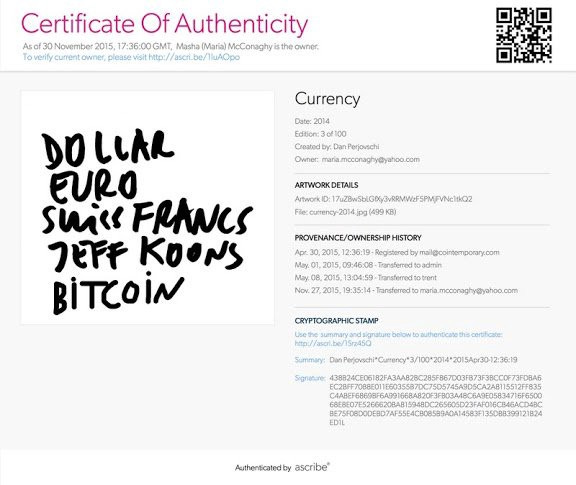

Other projects around that time also harnessed Bitcoin’s potential to verify scarcity and provenance for less memetic ends. Ascribe set out to create blockchain-based certificates of authenticity for artworks. Its founders, Trent and Masha McConaghy, came from Artificial Intelligence / Machine Learning and curatorial backgrounds respectively; the protocol was created, starting in 2013, in conversation with an array of artists producing digital work – Harm van den Dorpel and Constant Dullaart helped develop the beta – in an attempt to cure the widespread “online attribution problem”. While digital art had, by the early 2010s, attained major recognition in the offline art world, issues around its transfer, exhibition, and provenance still needed to be reckoned with: how could artists securely show, sell, and license their digital-born work?(11) There must have been a better way, and by the McConaghys’ assessment, it began with Bitcoin. Officially launched in 2015, Ascribe marketed itself as a way of registering provenance and IP on the Bitcoin blockchain. It boasted a wider range of sales actions than Counterparty, many of which were inherited from the legacy art market: with Ascribe, artists could make and register editions, and buyers (whether individuals or institutions) could consign and borrow the works they owned.

As one early employee explained, they weren’t really interested in developing a new market – rather, they were curious about how blockchain technology, with its public and immutable ledgers, could create more transparency into the existing one. Transactions were free, because they deliberately sought to avoid skimming profits from artists; the plan was to charge collections and archives rather than individual users. Centrally concerned with creating visibility and transparency around how assets moved through the art market, Ascribe stands out as an embodiment of the “hacker-engineer” ethos which, per Brekke’s figuration, sees blockchain technology as a way of fighting the centralized control of information to intervene in the infrastructure that shapes existing economic flows. And, to a certain extent, it took off. In 2015, the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Vienna purchased several editions of Harm van den Dorpel’s generative software artwork Event Listeners (2015), using Ascribe, and becoming the first art museum to pay for a new acquisition in Bitcoin. Van den Dorpel’s own Left Gallery used Ascribe for digital art sales until the platform paused in 2018. Hacked together in a way that Tim Daubenschütz, one of the developers behind Ascribe, recalls as “extremely avant-garde”, the platform elegantly addressed the critical issue of establishing provenance for works that live and circulate online – but it never quite found its niche. Some who were involved at the time suspect that, once the novelty factor of acquisitions like MAK’s had worn off, legacy institutions came to fear the market transparency that it sought to guarantee; others suspect it, like several prescient projects before it, was simply too early to market.

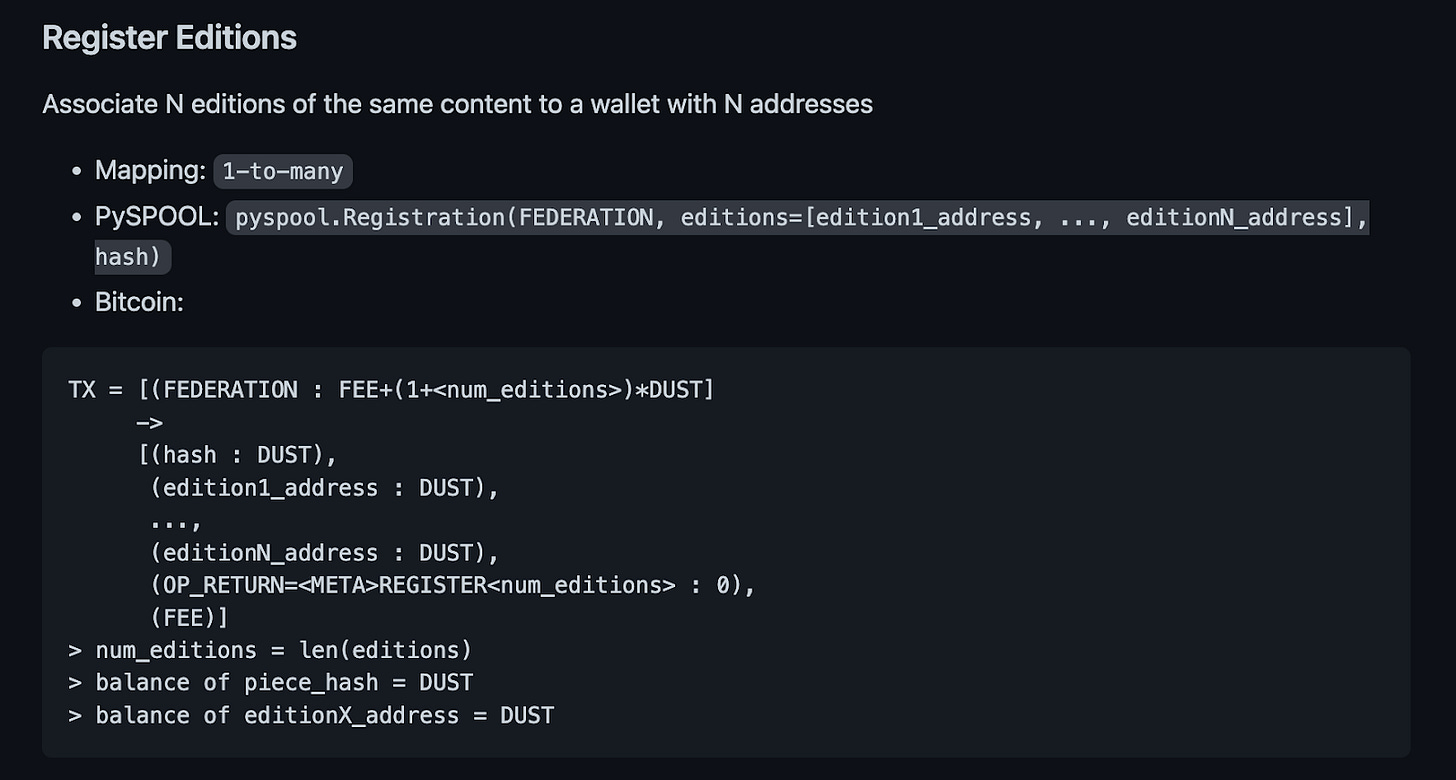

In either case, Bitcoin was ill-equipped to handle Ascribe, and it was sometimes met with outright hostility in the crypto community. On a technical level, Ascribe capitalized on a standardized function called OP_RETURN, which enables a user-defined sequence of up to 40 bytes to be written onto the blockchain. This allowed for things like links – pointing to images and longer texts living off-chain – to be stored in Bitcoin transactions. Daubenschütz wrote about the project in a recent newsletter for NFT curation protocol JPG.space: “Ascribe was built on Bitcoin … by signing up via email and password, a hierarchical deterministic wallet was derived from the federation wallet; all ownership transactions were stored in an inventive protocol called SPOOL, the “Secure Public Online Ownership Ledger”(12). Similar to the well-known ERC721 NFT standard, the SPOOL encodes ownership information on-chain(13); but it was a hell of a mess as Bitcoin really wasn’t meant for any of this.(14)” Indeed, issues occasionally arose with Bitcoin validator nodes rejecting the transactions for containing too much data; some hardcore Bitcoin purists even called OP_RETURN transactions “spammy” or blamed them for bloating the network (15). As their anxieties attest, Ascribe was a critical intervention for attempting to broaden the blockchain’s functionality beyond straight-up financial exchange.

ECOSYSTEMS OF MANY INTERWORKING PARTS

Around the time that this all was unfolding in the Bitcoin space, the blockchain that undergirds NFTs as we know them today made its way into the world. Ethereum – proposed by Vitalik Buterin in 2013, crowdfunded in 2014, and inaugurating its “Frontier Phase” on 30 July 2015 – offered smart contracts as a native functionality, weaving the capacity to store and execute self-enforcing code directly into its blockchain. While Bitcoin affords for some limited smart contract functions, Ethereum was built with a more expansive vision in mind. Its programming language, Solidity, is geared towards Turing-complete operations, unlike Bitcoin’s programming language, SCRIPT, which is tailored to monetary transactions.

These infrastructural differences entailed cultural differences in turn. Crypto-culture researcher Ann Brody suggests that Ethereum’s design as a virtual machine opens it up to a broader range of ideological orientations; its “world computer” imaginary positions it in line with what Lana Swartz calls “infrastructural mutualism” – a perspective that sees cryptocurrencies as a conduit to freedom of information and decentralization, not just decentralized finance, in step with the cypherpunk values that Brekke locates in the figure of the hacker-engineer (16). Drawing on earlier writing by Gabriella Coleman, Brody highlights the affinity for “tinkering” in the Ethereum ecosystem; borrowing Christopher Kelley’s formulation of the “recursive public”, she explains how the network’s creation through feedback shapes its own means of existence (17).

Ethereum’s openness and programmability, along with its community-driven development process, necessitated the adoption of universal token standards – certain commonly agreed-upon specifications around how tokens are created and deployed – to ensure compatibility between different developments across the blockchain. In Ethereum’s case, the ERC, or Ethereum Request for Comments, is the most basic application-level standard. The protocol for creating ERCs to facilitate the definition of future standards was laid out by a community of developers – not Ethereum employees, but hobbyists and dApp-designing dreamers – in the network’s early days. “What’s unique about blockchains like Ethereum”, Dieter Shirley, CTO of Dapper Labs, tells us, “is that they aren’t just pieces of software, but ecosystems of many interworking parts.” Community proposals can submit ideas for improving those parts, but they can also introduce new parts altogether. (18)

Like Bitcoin, Ethereum’s code is open source, meaning no single entity owns or controls it, and developers are encouraged to “fork” code, re-use existing functionality, and iterate on what others have already built. Crucial to recognize, the same open source spirit runs through the proposal process through which the protocol itself has been architected and elaborated. Not only the code, but the procedure for submitting and formalizing it, are developed by interested individuals on public fora, and have been from the outset (19). As the “recursive public” builds (or “buidls”, as the meme goes), new possibilities, each with the potential to reshape the network, come into being.

Original proposals for “standardized contract APIs”, as they were conceived of around the time of the Frontier launch, focused on “coins” rather than “tokens”, aiming to provide basic and universal functionality for transferring and spending tokens within smart contracts. The first “coin standards” were discussed at Devcon1 in London, and the debate around their specifications continued in a GitHub “gist” (or online code snippet) created by Fabian Vogelsteller. Joseph Chow proposed ERC-19, an early coin standard that was abandoned in favor of Vogelsteller’s thread, EIP-20, which eventually, in November of 2015, became the ERC-20 token, the fungible token standard still widely in use today. ERC-20 formed the minimal technical standard for all Ethereum smart contracts; to this day, all other Ethereum tokens building beyond it must follow the rules that it defines (20).

The process of proposing and formalizing new token standards continued following ERC-20, unfolding through a similar process to the advent of ERC-20. Ethereum Improvement Proposals, or EIPs, are submitted as draft standards and presented in a GitHub repository for review and discussion. They’re shared widely to gather community interest, circulating on Web2 social media like Reddit, Twitter, and Discord. After feedback and revision, if they make the cut, they’re eventually pronounced “FINAL” through an “ALL CORE DEVS CALL” that achieves rough consensus. The proposals are then recognized as numbered ERCs, and accepted as standards for the Ethereum community to implement across their projects (21). Simon de la Rouviere, who led the standards panel at Devcon1, explains that “An EIP is a document created by the community that formalizes a specific way to improve Ethereum […] It's important as a tool to gather, form, discuss, and formalize improvements and changes to the ecosystem.”(22) Billy Rennekamp offers a similar explanation of the EIP process, adding that “it’s basically a way for engineers to discuss standardizing a way to do something with software so that everyone does it the same way […] it makes it possible to have predictable interactions.” “Because Ethereum and other blockchains are operated by a large number of third parties,” he continues, “there’s no possibility of enacting change from a singular actor. It is the ‘populus’ that must agree to enact the idea in the end.”(23)

The hacker-engineer ethos that animated Ethereum’s early development also resonated with technologists like John Watkinson and Matt Hall, who, working under the name Larva Labs, released CryptoPunks on 23 June 2017. Influenced by the aesthetics of “misfits and nonconformists” from the London punk movement of the 1970s to cyberpunk worlds like Blade Runner and Neuromancer, CryptoPunks comprised a script that generated 10,000 8-bit pixel art characters with random combinations of variously distinctive (and variously rare and sought-after) features: people, zombies, apes, and aliens swagged out with drip like 3D glasses, cigarettes, and Mohawks (24). Each Punk is unique, though at the time of the project’s release, there was not yet a formal standard for non-fungible Ethereum tokens; CryptoPunks’ token infrastructure built on ERC-20, the primary accepted standard at the time, but foretold the market for non-fungible tokens that would come soon after. In parallel, the first virtual worlds on Ethereum, like Decentraland, were being built. First successfully deployed to a testnet in 2017, and launched publicly in 2020, Decentraland – developed by Manuel Araoz, who had shipped the Bitcoin-based registry service Proof of Existence in 2013 – created an environment, like the game-worlds of early XTP-based trading card projects before it, where ownable digital assets had evident value.

By autumn of 2017, the idea of creating a new standard for unique tokens was still early and relatively niche, despite CryptoPunks’ successful sale (25). Building on the emerging idea, Dieter Shirley opened the conversation towards EIP-721 (which William Entriken, Jacob Evans, and Nastassia Sachs would later contribute to). “When I proposed EIP-721 (which then became ERC-721), the notion of non-fungible tokens was nascent at best,”(26) Shirley recalls. At that moment, there was little interest in establishing an official standard for non-fungible tokens, even despite the history of art-related Bitcoin initiatives that testified to the utility of unique, verifiable ownership and provenance. The proposal to create a non-fungible token standard needed a visible justification; it had to map to something meaningful for the Ethereum community to comprehend its utility and importance.

This landmark moment of consolidating meaning came, timed to a bullish crypto market in November 2017, in the form of a cat game. Why bother architecting a new standard for unique, ownable tokens? The allure of trading and breeding genetically-distinct cartoon felines proved one compelling reason. Developed by Dapper Labs and illustrated by Guile Twardowski, CryptoKitties set forth a fun and understandable use-case for non-fungible tokens. The CryptoKitties “White Paepurr” touches on the appeal of digital collectibles that earlier Bitcoin projects like Counterparty and Ascribe helped establish, though it doesn’t refer to these outright; instead, it draws from gaming, where in-game assets in World of Warcraft and the Steam marketplace have long commanded real-world valuation. It also names CryptoPunks as a point of reference, arguing that the early surge of interest in the Punks waned “due to their lack of functionality” (27). CryptoKitties set forth with a clear function: the game was purpose-built to elucidate the possibilities of unique tokenized assets. It created a gamified, approachable brand – and furthermore, a community. It was to be upheld by a sustainable revenue-based business model, not an ICO, and this sustainability was uniquely enabled by the affordances of the blockchain. Hence, the White Paepurr outlined, and CryptoKitties embodied, the first significant use-case for ERC-721.

NFTs as we know them today are more or less in line with the model that CryptoKitties exemplified, adhering to the ERC-721 token standard (28). ERC-721 NFTs are comprised of three main components: a smart contract, a numeric identifier, and metadata typically including a name, a description, and a location pointing to the digital asset that the token represents. Wilkins Chung, the cofounder of Manifold, offers a good technical run-through of how it all fits together: The smart contract serves as a ledger, collecting the record of ownership that comprises the NFT’s provenance. The smart contract and identifier guarantee that the token is provably unique, and the contract contains the functions necessary to look up the metadata – which can be stored “on-chain” or off-, in another file system like IPFS, a file storage blockchain like Arweave, or good old Amazon Web Services(29). This setup is true for NFTs all Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM)-based blockchains; it is also the case for NFTs on Tezos (which follow the TZIP-12 token standard) (30).

CRYPTOART AND THE MARKET(PLACE)

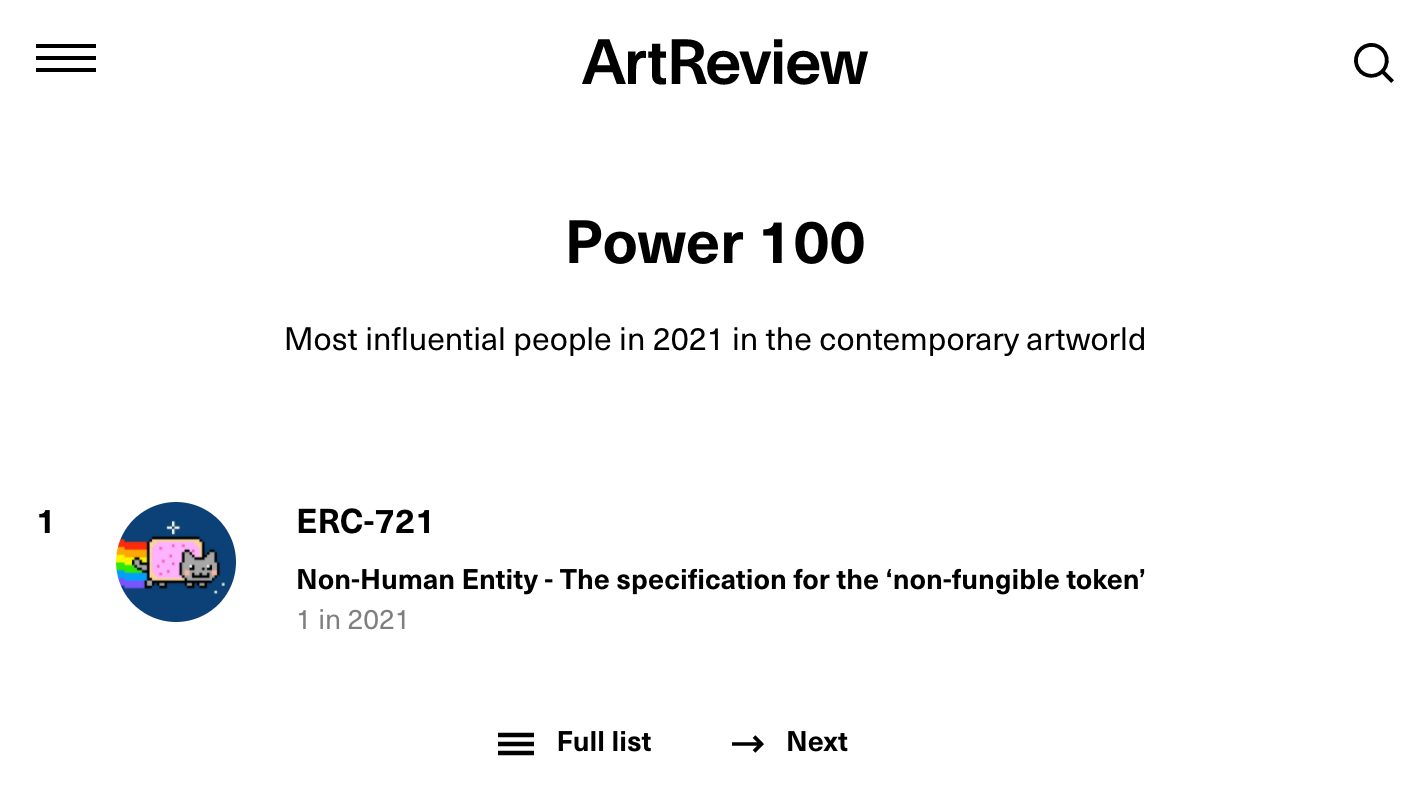

Following CryptoKitties’ smash success came a Cambrian Explosion of NFTs that further proved its central assertion: NFTs create a visible purpose for smart contracts beyond cryptocurrency. Between 2018 and the present, the number of innovative NFT projects worth remarking on is too great to even begin to gloss here (31). Most of these (at least the ones on Ethereum – there’s also a rich ecosystem of NFTs on other blockchains, like Solana and Tezos) have sat on the same token infrastructure that CryptoKitties established (32). With a dramatic ascent in the summer of 2021 as blockbuster NFT sales rocked the legacy art world, ERC-721 even topped the year’s ArtReview Power 100, outranking the likes of Larry Gagosian and David Zwirner on the publication’s annual list of the most influential people (or in this case, non-human entities) in contemporary art.

The infrastructure of the NFT space has far from stopped evolving since then. Since ERC-721, the primary locus of innovation has shifted from the creation of new token standards towards the elaboration of other kinds of infrastructure. Different kinds of marketplaces have cropped up, alongside platforms that offer new tools to empower creators and user-friendlier ways of interacting with smart contracts. These innovations build towards giving artists more creative control over how their work is presented and experienced, in addition to broadening the audience that can access it or find it meaningful (33).

Some of the sales platforms that have emerged in this explosive moment, like the curated marketplace SuperRare, launched in April 2018, replicated the sales mechanics of the legacy art world. But in certain critical ways, it also diverged, opening the door to a generation of crypto-native artists. (The original creator of an NFT sold on SuperRare is entitled to 10% of secondary sales, for instance – a practice infamously hard to enforce and far from standard in the offline art world.) Others, like OpenSea, which began in December of the previous year, are less precisely tailored to art but have created a vibrant economy for all kinds of digital collectibles. A vast majority of Ethereum NFTs index to OpenSea, and many websites, including JPG.space and various aggregators, pull from the OpenSea API. It’s therefore the largest secondary market discovery platform for Ethereum (along with other chains like Polygon, Klatyn, and Solana); its nearly comprehensive range makes it a popular price indicator and a point of reference for other marketplaces. Minting is completely open (for better or worse), meaning that anyone with enough ETH in their wallet to pay gas fees can list an NFT of their own. But it’s also, crucially, centralized. NFTs minted on OpenSea are locked into the platform, and works can be taken down at any time for any reason. These drawbacks have catalyzed a litany of projects that, in various ways, attempt to break free from the OpenSea API.

One alternative came in the form of ArtBlocks, a marketplace launched in 2020 specifically for generative art, appealing to creative technologists and software-literate collectors. ArtBlocks founder Erick Calderon, a practicing artist himself, cites CryptoPunks as inspiration, seminal in demonstrating the synergy between randomly-generated code based art – historically difficult to preserve or market – and blockchain technology. Other boutique publishing platforms like Folia, which launched in February 2021, have also emerged to give artists greater agency over their smart contracts and offer a more bespoke front-end exhibition interface. Foundation also emerged in February 2021, with a similar structure to SuperRare. It resonated with the offline art world thanks to curator Lindsay Howard’s touch; like SuperRare, though, it distinguishes itself from the legacy art world by guaranteeing artists a cut of all future secondary sales on its platform.

CONCLUSION: MAINTAINING DECENTRALIZATION AND CREATIVE SOVEREIGNTY

Beyond this profusion of (admittedly centralized) marketplaces, it is readily becoming possible for creators to design and deploy their own, generating new possibilities for NFT exhibitions and sales that push against the Web2-esque tendency towards platform monopoly. The block explorer EtherScan, founded in 2015, makes deals from all marketplaces transparent and searchable, displaying public information about transactions carried out across the Ethereum blockchain. While not a marketplace itself, EtherScan does allow minting directly from smart contracts – a feature that projects like Loot (2021) took advantage of by cleverly enabling people to claim NFTs freely using the block explorer’s inbuilt “write contract” function.

It’s also common to build one’s own marketplace as an interface for minting and selling – but this can be prohibitively challenging for creators who aren’t comfortable writing their own smart contracts in Solidity. However, these barriers to accessibility are lowering thanks to projects like (the a16z-funded) Manifold, which launched Manifold Creator, an open-source smart contract, in May 2021, followed by Manifold Studio, a friendly user interface for minting with it, that December. Striving to do away with the idea of an intermediary platform altogether – their mantra, cofounder Wilkins Chung tells us, is “the creator is the platform” – Manifold’s tools make it possible for artists who don’t know how to code in Solidity to customize the smart contracts behind their NFTs.

“There are a significant number of 'public utilities' that need to exist for the NFT ecosystem to prosper and maintain decentralization and creative sovereignty”, Chung explained to us in an email interview. Another such utility, Zora, launched in a similar spirit shortly before Manifold Creator, in January of 2021. Together, platforms like these have heralded a re-decentralization of the NFT ecosystem. NFTs minted with the Zora protocol can be bought and sold across platforms, rather than being locked into the marketplace of their creation; being as it is a protocol rather than a conventional marketplace, the platform takes no fees and allows artists to set their preferred percentage cut for secondary sales.

Zora founder Jacob Horne has since elaborated the idea of “hyperstructures”, or free and permissionless crypto protocols that can run in perpetuity without charging user fees or relying on intermediaries. Hyperstructures resonate with the original vision of dApps that Gavin Wood laid out in his seminal 2014 blog post, “What Web 3.0 Looks Like” – secure, open, trustless, and interoperable systems for communication(34) – and further advance the lineage of hacker-engineering, especially with their emphasis on business models that do not rely on the extraction of user data as a source of value. “The nature of the medium of token ownership and unstoppability means we no longer need to extract profits to realize value creation”, Horne explains (35). Some companies building Web3 protocols have more explicitly shifted to adopt this approach in early 2022, including Fractional, Verse, and 0xSplits (36).

Standing by the claims and tenets of web3 rhetoricians, the next innovations in NFT infrastructure must continue to elaborate the values – non-extractive revenue models, permissionlessness, unstoppability, and censorship resistance – that animate projects like these. The obligation to speculate towards better futures, to build as a form of critique, recurs across Wood’s and Horne’s writing; it echoes Andreessen; it resonates with Chandler and Lippard. Perhaps it will catalyze the next cycle in this entangled, open-source loop. The infrastructural innovation that enabled NFTs – and the cascade of hyperstructures that they have made possible – is a polyphonic history, its hacker protagonists continually shaping the ever-expanding field. This brief overview of that history is partial and contingent, as any timeline will necessarily be. It’s not closed, nor teleological, and others can and ought to be created. Like the infrastructural development of NFTs itself, this history is replete with open-source processes, underpinned by building and hacking that allow new forms of culture to emerge and proliferate. This iterative, collective process must be represented as complex and visible, foregrounded in the forums (like this one) where canons of digital art are built and rebuilt.

Footnotes:

Jaya Klara Brekke (2020): Hacker-engineers and Their Economies: The Political Economy of Decentralised Networks and ‘Cryptoeconomics’, New Political Economy, DOI: 10.1080/13563467.2020.1806223

https://cast.b-ap.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2011/09/lippard-theDematerializationofArt.pdf

It’s worth noting that the emergence of contemporary NFT infrastructure was propelled by people working on similar projects in parallel and complimentary, while not explicitly interrelated, ways. Numerous artists and tech founders were interviewed as part of the research leading up to this essay, and most of them saw retrospective connections between their work and others’, but overwhelmingly claimed to have little awareness of similar initiatives in the landscape at the time. In short: the history itself has unfolded in a decentralized manner.

In the interest of factual accuracy, we have opted to give months and years, rather than specific dates, when the exact timing of a project or development is unclear in the historical record.

Foreshadowing a contemporary line of critique against NFTs: these coins’ relationship to the physical goods they represented only existed insofar as the people trading them agreed to enforce it.

https://counterparty.io/docs/broadcast/

In contrast to Mastercoin, which raised around 100k with an ICO, or “initial coin offering”, Counterparty distributed its native currency, XCP, using “proof-of-burn”: the developers, just like everyone else who wanted to acquire the tokens, had to get them by sending the corresponding amount of Bitcoin to an unrecoverable wallet address. In this sense, Counterparty embodied the spirit of decentralization from the outset: risk was distributed equally across its founders and devs, who obtained XCP by destroying bitcoins just like the rest of the protocol’s early adherents. An ICO would also have situated whoever held the money from the sale as a single potential point of failure – so the early decision to fund Counterparty with proof-of-burn also set it up for longevity, which could help explain the fact that it’s still in use today.

The BitcoinTalk forum where Lerner launched NILIcoins is also marked with a warning: “One or more bitcointalk.org users have reported that they strongly believe that the creator of this topic is a scammer. (Login to see the detailed trust ratings.) While the bitcointalk.org administration does not verify such claims, you should proceed with extreme caution.” https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=782161.0

https://anildash.com/2021/11/14/i-didnt-invent-nfts-but-we-dont-really-have-any-other-way-to-talk-about-tech/

Unlike other early Bitcoin-based initiatives coming directly out of the art world, the Pepe trade has been celebrated by the Bitcoin community. At least one Pepe trading card experiment on Ethereum, called “Peperium”, was proposed on online forums, but never managed to take off. This might invite conclusions about the ideological landscape of Bitcoin vs. Ethereum, in step with research carried out by Lana Swartz and Ann Brody, both of whom conclude that Ethereum is more aligned with cypherpunk libertarianism and “infrastructural mutualism” while Bitcoin slants towards a post-Randian crypto anarchism.

The Ascribe whitepaper summarizes these challenges by asking, among other questions: Was Molly Soda really just supposed to sell webcam videos on a flash drive?

https://github.com/ascribe/spool#spool

https://github.com/ascribe/spool#transfer-ownership

https://jpg100.substack.com/p/the-jpg-newsletter-with-my-friend?s=w

Reactions like this one were common across the #bitcoin IRC channels in the mid-2010s.

Brody, Ann, & Couture, Stéphane. “Ideologies and Imaginaries in Blockchain Communities: The Case of Ethereum.” Canadian Journal of Communication 46(3), 543–561.

Ibid, 545

11 April 2022

Anyone with a GitHub account can, in theory, contribute to Ethereum. The various possible ways to contribute, including working on open issues and adding developer tools, are outlined on https://ethereum.org/en/contributing/, along with the names and PFPs of the community members who have contributed so far. There are 770 as of this writing.

For the real heads: ERC-20 outlines six basic coding functions central to token implementation, which must be uniform across all tokens in the Ethereum ecosystem: “TOTAL SUPPLY”, “BALANCE OF”, “ALLOWANCE”, “TRANSFER”, “APPROVE”, and “TRANSFER FROM”.

The list of accepted token standards is maintained at https://eips.ethereum.org/erc.

Via email to the authors, 9 April 2022

Via telegram chat with the authors, April 2022

https://www.christies.com/features/10-things-to-know-about-CryptoPunks-11569-1.aspx

Larva Labs’ website states that CryptoPunks served as “the inspiration for the ERC-721 standard”; this claim is subjective and tough to evaluate, but one could easily cast it in gentler terms and note that the Punks crucially shaped the thought-space surrounding digital collectible art assets.

Via email to the authors, 11 April 2022

CryptoKitties White Paepurr V3, pp. 5

Interesting to note, CryptoKitties actually launched before the final proposal for ERC-721 was accepted; it uses v0 of the token standard, not the community-formalized v1, which came in January 2018.

Via email interview with the authors, 13 April 2022.

Solana functions differently than these blockchains: its NFTs come out of a singular Solana Token Program, which enables the minting, transferring, and burning of both fungible and non-fungible tokens; instead of deploying a new smart contract for each new token, actions are carried out by sending an instruction to the token program.

Of course, many of these projects are explored in depth throughout On NFTs.

Other token standards have been adopted following ERC20, including ERC223 and ERC777, both of which attempt to address design flaws in ERC20 that make it possible to send tokens unrecoverably to a smart contract. However, neither has been widely adopted yet, and no new token standard has created such widely-used new functionality as ERC721.

Perhaps this turn towards marketplace innovation has underscored another axiom: contemporary art is inextricable from markets. This fact, often only hesitantly-acknowledged at best in the legacy art scene, is a fundamental part of this new world: NFTs don’t so much financialize art as highlight how art has always been financialized.

https://gavwood.com/dappsweb3.html

https://jacob.energy/hyperstructures.html

Fractional (fractional.art) enables people to buy and sell fractionalized shares of NFTs; Verse (verse.xyz) self-describes as a “hyperexchange protocol”, and 0x Splits (0xsplits.xyz) is a protocol for splitting onchain income.